Ilocano faith traditions.

Cathedral of St. William, Laoag, Ilocos Norte. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Indigenous beliefs.

Before the Spanish came with their churches and bells, the Ilocano people already had a strong faith.

They believed the world was full of spirits. The mountains, rivers, trees, and even the wind could hold unseen powers that shaped daily life.

Deities

Above all was Kabunian, the god of the sky and creator of life.

But most of the time, people dealt with the spirits close to them—the ones who lived in their homes, fields, and villages.

Some spirits protected families and crops, while others caused sickness or trouble if not respected.

Ancestors also remained part of life. When someone died, their spirit did not leave forever. They stayed near, watching over their family.

To keep peace with them, people offered food, drinks, and prayers. A happy ancestor spirit could protect the family, but a forgotten one might bring harm.

Religious leaders

When problems came—like illness or poor harvests—villagers called on ritual leaders called manag-anito.

These healers prayed, sang, and sometimes sacrificed a chicken or pig to restore balance between humans and spirits.

People also looked for signs in dreams, bird calls, or the weather, believing the spirit world spoke through nature.

Syncretism

When Catholicism arrived, many of these old practices blended with new beliefs.

Even today, Ilocanos may pray at family graves, offer food at festivals, or keep traditions that echo the old ways—despite dogmatic rules against these practices.

At the heart of it all is the same belief that the human world and the spirit world are close together, and living well means keeping them in harmony.

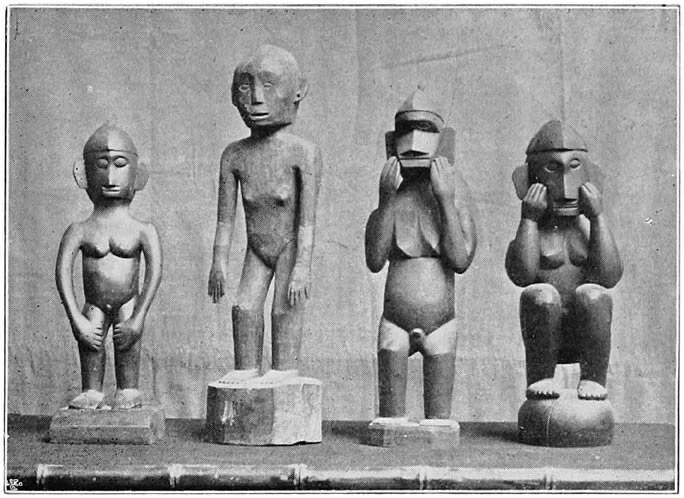

Anitos of the Ilocano people, 1900. Photo: Frederic H. Sawyer.

Deities of the Ilocanos.

Supreme deity

Kabunian (Apo Kabunian, Maykapal)

High god of the sky; seen as creator and giver of life; honored with respect but often distant; most prayers went to spirits closer to daily life.

Ancestors and household spirits

Anito / Kadkadua

General term for spirits of both ancestors and nature; ancestors were believed to protect the living when remembered with offerings.

Lakay-lakay and Baket-baket

Ancestral old man and old woman spirits; guardians of family and home.

Deities of nature

Apo Laud

Spirit of the sea, feared and respected by fishermen.

Apo Litao

Spirit of the sun.

Apo Tinguian

Spirit of the mountains and forests.

Karinga

Spirits of great trees, rocks, or natural landmarks.

Sirit

Water spirits living in rivers, streams, and wells.

Tricksters

Al-ali

Mischievous forest beings, sometimes tricksters; could help or harm depending on how they were treated.

Spirits of illness and misfortune

Manggagat

Malevolent spirits thought to bring sickness.

Mansisit

Spirits that “sat” on people, causing fever or weakness.

Mangmangkik

Child-snatching spirits, often used as warnings to children.

Survival of the beliefs

Many Ilocanos today use the name Kabunian to refer to the Christian God. Folk practices, like offerings during harvest or prayers at graves, still carry echoes of these older traditions.

The old faith was not a single pantheon of deities but a layered world. There was one high god in the sky. And there were countless spirits in daily life—there were both kind and dangerous.

Laoag bell tower. Photo: Raniel Jose Castaneda via Wikimedia Commons.

Timeline of faith.

Indigenous beliefs before the 16th century

Ilocanos practiced animism like worship of Kabunian the sky god, spirits of nature, and ancestral souls called anito.

Ritual specialists called manag-anito led ceremonies for healing, harvest, and protection.

Arrival of the Spanish in 1572

Massive stone churches were built, blending European styles with local design.

Catholic fiestas and devotions to saints became central to Ilocano life.

Spanish defeat and arrival of the Americans in 1898

After the Spanish–American War, Protestant missionaries arrived with U.S. colonial forces.

Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists established schools and churches, especially in urban centers.

Philippine Independent Church founded in 1902

Also called the Aglipayan Church.

Led by the Rev. Gregorio Aglipay, a former Catholic priest of Batac, Ilocos Norte.

Formed as a nationalist response to centuries of hardline, authoritarian Spanish control of the Church in the Philippines.

Became the second-largest Christian denomination in Ilocos, with strong roots in the region.

It is a member of the worldwide Anglican Communion and in full communion with The Episcopal Church in the U.S.

Growth of Protestant schools in the 20th century

Institutions like Northern Christian College in Laoag spread Protestant influence.

Protestant faiths remained smaller compared to Catholicism and Aglipayan but had lasting impact.

Founding of Iglesia ni Cristo in 1914

Iglesia ni Cristo was established in Manila by Felix Manalo, but its influence spread nationwide.

By mid-20th century, congregations had formed in Ilocos towns and cities.

It has largely been maligned by Catholics as a cult.

Evangelical expansion in the late 20th century

Evangelical and Pentecostal churches—often called “Born-again” churches—grew rapidly.

Groups like Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witness or Saksi ni ‘Hovah also established footholds.

A plural but Christian landscape today

Roman Catholicism remains the majority faith

Diocese of Alaminos

Diocese of Cabanatuan

Diocese of San Fernando de la Union

Diocese of San Jose de Urdaneta

Archdiocese of Nuevo Segovia

Diocese of Baguio

Diocese of Bangued

Diocese of Laoag

The Aglipayan Church holds a unique role in Ilocano identity and nationalism.

Protestant, Iglesia ni Cristo, and Evangelical communities continue to grow, especially in urban centers.

Indigenous traditions survive in blended practices like harvest rituals, grave offerings, and folk healing.