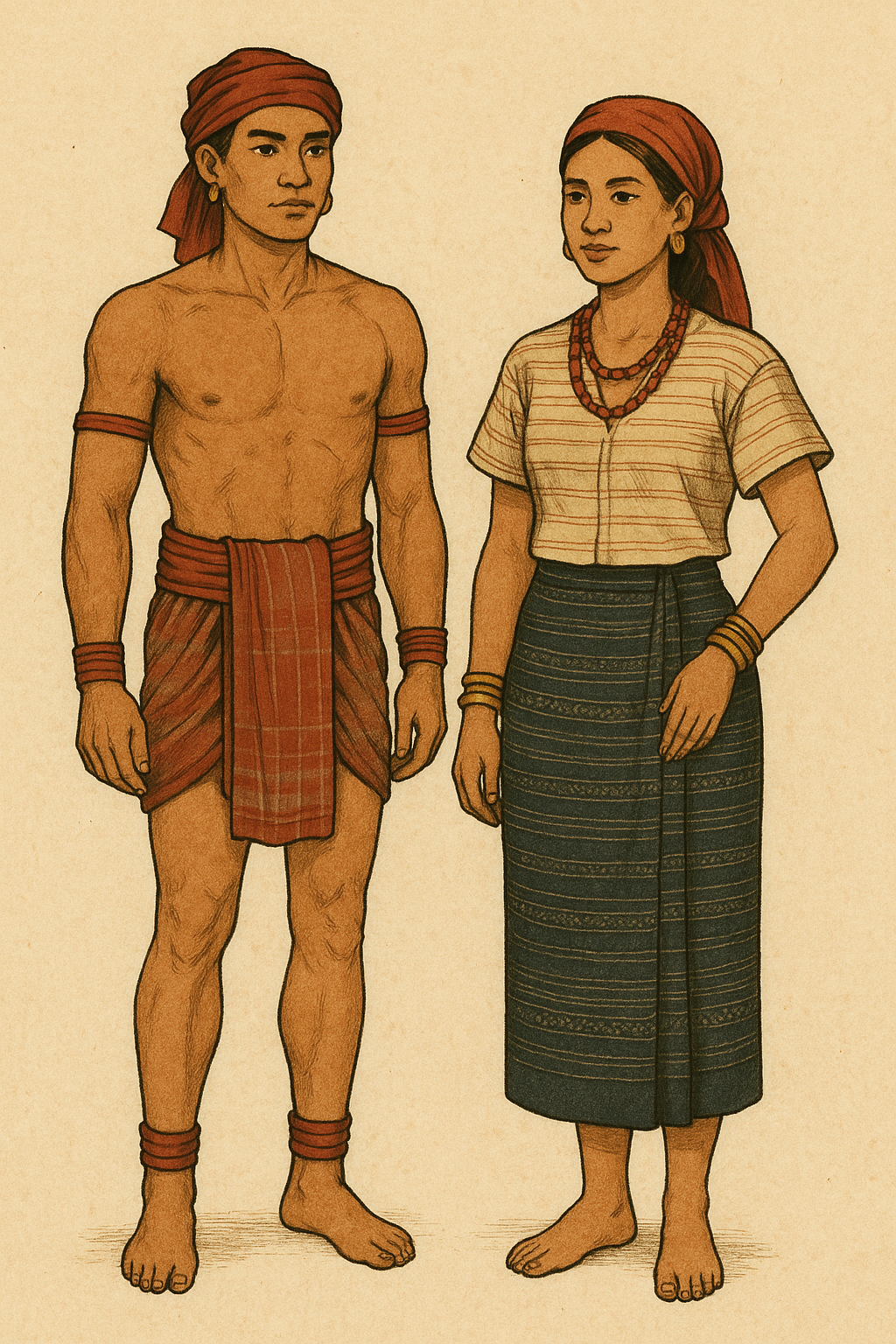

Historic Ilocano clothing.

How Ilocanos once dressed.

Imagine walking into an Ilocano village centuries before the Spanish arrived. The air is warm from the sea breeze, and the first thing you notice is the deep blue of indigo-dyed cloth drying in the sun. Woven by hand on simple looms, the fabric carries stripes and patterns that reflect the skill of the weaver.

The men move about in ba-al, a wraparound loincloth knotted at the waist. Some leave their chests bare, their skin marked by tattoos that tell stories of battles and bravery. Warriors and leaders might wear a headcloth, a putong, wrapped neatly around the forehead to show rank and pride. On cooler days or during gatherings, a woven cloak or sash is draped across the shoulder, its colors richer than everyday wear.

The women wear tapis, skirts wrapped around the waist and falling gracefully to the knees or ankles. The fabric is soft cotton, often dyed with the same indigo that stains their fingers from weaving. Some women wear a simple blouse or breast covering, while others, especially from wealthier families, add layered skirts or more finely woven cloth. Necklaces of beads or brass glint in the light, and bangles chime softly as they move.

Both men and women treasure ornaments. Shells from the sea, beads traded from faraway lands, and sometimes even gold are worn as earrings or necklaces. These are more than decoration—they are signs of dignity, wealth, and connection to ancestors.

The clothing is simple, yes, but it is alive with meaning. The stripes on a skirt speak of family skill, the tattoos on a man’s chest declare his courage, the shimmer of a bracelet shows the fruits of trade. Together, these garments and adornments weave a picture of a people rooted in their land, proud of their craft, and aware that dress, like language, tells the world who they are.

The barong is not Ilocano.

The official national men’s dress of the Philippines known as the barong Tagalog is not an indigenous Ilocano garment. It is even named after the ethnolinguistic tribe from which it comes.

It is historically associated with Tagalog lowland elites in Luzon, especially in areas like Manila, Laguna, Batangas, and Cavite.

The barong emerged during the Spanish colonial period as a formal male garment made of sheer fabrics like piña, jusi, or abacá. It was much more suited for the warmer, more humid climate of the Manila region where Spanish authorities ruled the archipelago.

When Tagalogs were sent to the Ilocos to promote Tagalog assimilation and language use, this included the use of the barong.

Aware of the barong as a tool of assimilative colonialism over the Ilocanos, Millennials and younger Gen Z nativists are promoting a return to formal dress that hearken back to more indigenous fashions before the imposition of Tagalog styles.

So what did formal wear look like?

For men, the formal look was a white camisa de chino—a shirt similar to the Chinese-cut dress shirt made of silk. Or, they wore a simple long-sleeved shirt of inabel, often tucked into dark trousers, with a wide woven belt or sash.

For women, it was the baro’t saya (blouse and skirt ensemble) with a tapis, woven in abel Iloco. The tapis was so common among Ilocanos that even in the 20th century, photographs often show Ilocano women wearing it as a marker of their heritage.

Depictions resembling traditional Ilocano merchants. These show practical dress and woven hats that resemble the “kattukong,” a traditional Ilocano headgear that persists into later periods.

Pre-colonial

After colonization by Spain. Notice the Chinese-cut collar of the men's shirt.

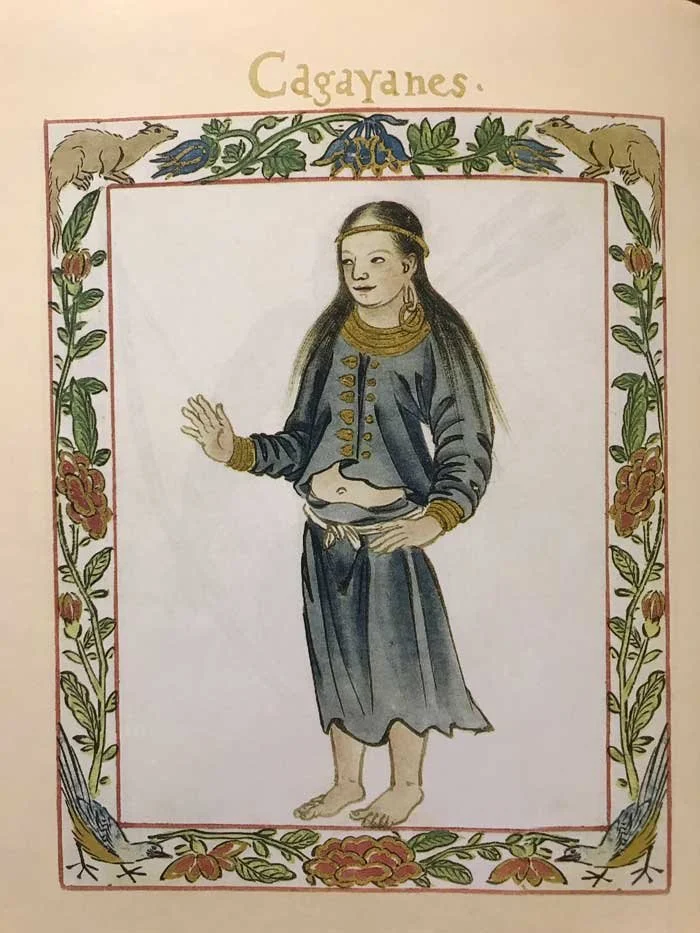

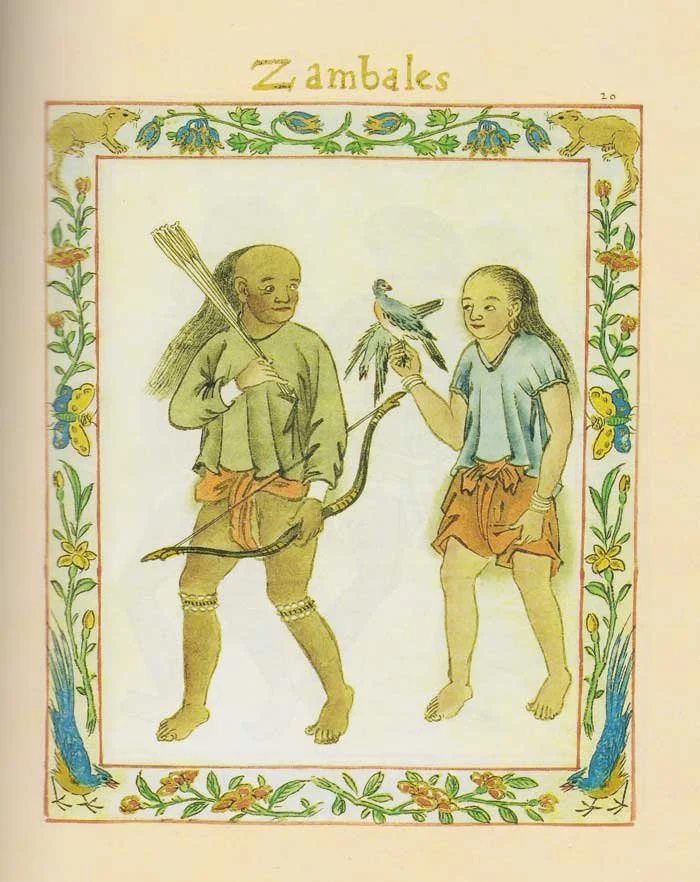

Illustration from the Boxer Codex (c. 1590). This provides rare visual insight into what early Ilocanos and neighboring groups may have worn, including hairstyles and basic attire.

Illustration from the Boxer Codex (c. 1590). This provides rare visual insight into what early Ilocanos and neighboring groups may have worn, including hairstyles and basic attire.

Inabel weaving.

Image: Gerald Farinas.

Inabel weaving is a traditional textile art of the Ilocano people. The word inabel comes from the Ilocano verb abel, meaning “to weave.”

It refers both to the process of handweaving and the finished woven cloth.

Inabel fabrics are made on wooden looms, often using cotton thread that is handspun and hand-dyed.

Key features

Designs and patterns

Inabel textiles feature geometric patterns, stripes, and symbolic motifs. Some represent natural elements like rivers, mountains, or animals; others symbolize cultural values such as protection, fertility, or prosperity.

Durability

Inabel is known for being strong and tightly woven, which historically made it ideal for blankets, garments, and everyday household textiles.

Colors

Traditionally, natural dyes were used, producing earthy tones. Today, brighter synthetic dyes are also used.

Cultural significance

Inabel weaving is centuries old, practiced long before Spanish colonization.

It was traditionally a community and family skill, passed down through generations, especially among women.

The textiles carry cultural identity and pride, representing Ilocano artistry and resilience.

Modern use

Today, inabel is still woven in Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, Abra, and La Union. It is used not just for blankets and clothing but also for fashion pieces, home décor, and accessories, helping keep the craft alive while providing livelihoods to weavers.