Sugar and Soil: How a U.S. Census map connects my Hawaii Ilocano forefathers with Germans

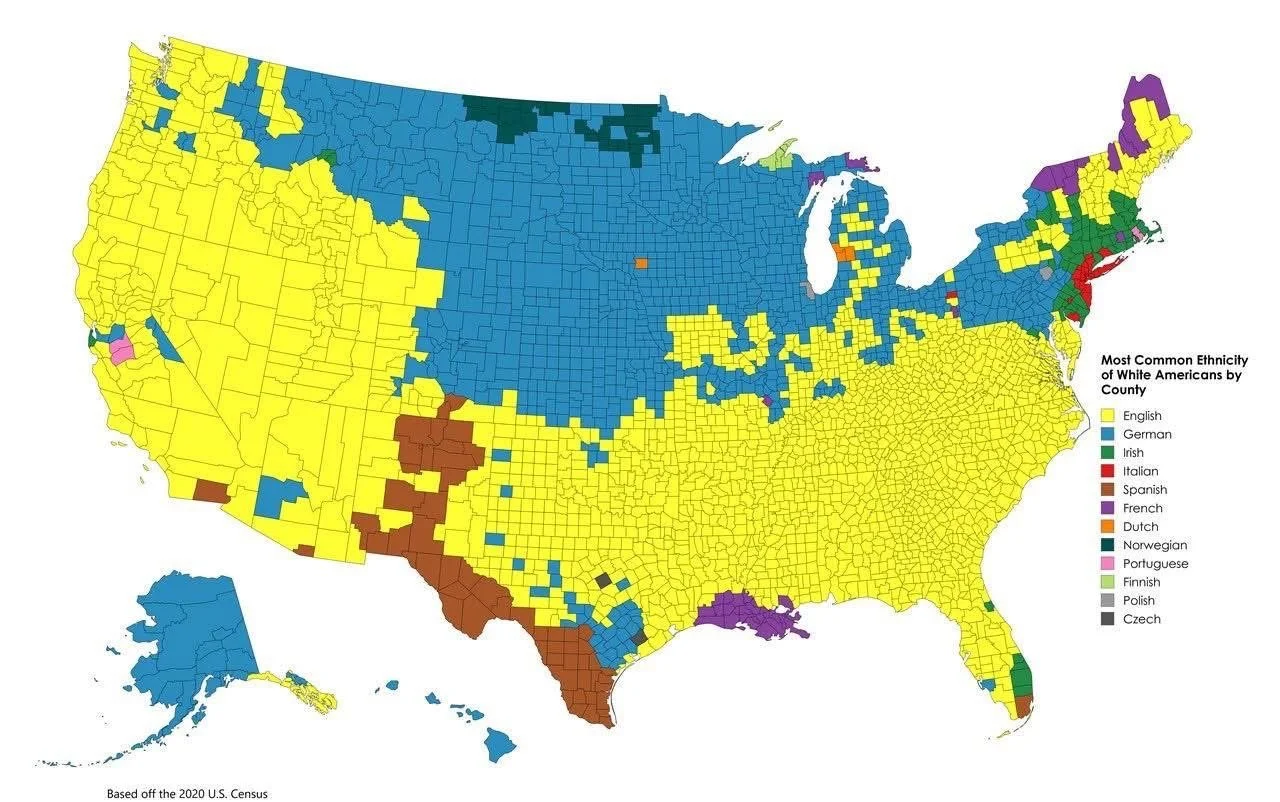

Map of largest white ancestries in each state based on 2020 U.S. Census data.

It looks almost like a piece of modern art at first glance. The 2020 U.S. Census map is a kaleidoscope of color, with sharp county lines filled in like a quilt of family histories.

The Midwest glows deep blue for German ancestry, while shades of green sweep across the Northeast, marking Irish roots. Yellow sprawls over the South and West, symbolizing English heritage, and patches of purple pop in New England for French settlers. Each block of color represents people and their migrations, choices, and hardships.

It is a simple map of white ethnic ancestry, but it holds a mirror to the broader story of America.

For me, it is also a reminder of my own family’s journey, which began far from the U.S. mainland and is deeply tied to the sugar fields of Hawaii.

Life before the cane fields

My grandparents grew up in northern Luzon, in the Ilocos region. Life there was hard. The soil was dry, farms were small, and opportunities were scarce. When recruiters from the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association came through their villages promising steady wages, housing, and a chance to start anew, many young men and women signed up. For them, Hawaii was a dream, a far-off land where work and dignity seemed possible.

When they arrived, the reality was harsher. They found themselves in tightly controlled plantation camps, where every aspect of life was overseen by the company. They lived in cramped housing, paid rent to their employers, and shopped at company stores that kept many workers trapped in debt. The sun in Hawaii was as relentless as it was back home, but now they labored under a system designed to exploit them.

German Hawaii

By the time Ilocanos arrived in Hawaii, German immigrants had already established themselves as powerful players in the sugar industry.

Heinrich Hackfeld arrived in Honolulu in the 1840s, and his business, Hackfeld and Co., grew into one of the most powerful firms in the Pacific. It later became Amfac, a name still tied to Hawaii’s economic history.

Other Germans came as merchants, ranchers, and plantation owners. Some married into Hawaiian royalty, owned vast tracts of land, and held high political offices in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Their influence helped cement the plantation system that recruited workers like my grandparents. German names appeared everywhere: on company letterheads, store signs, and the ledgers that tracked the lives of cane field laborers.

Ilocanos: Hawaii’s backbone

Ilocanos became the largest group of Filipino workers in Hawaii. Their resilience earned them a reputation for being strong and hardworking, a stereotype born from necessity rather than choice. Over time, Ilocanos built communities, sent for their families, and laid roots that transformed Hawaii’s cultural fabric.

The sound of Ilocano became as familiar as English or Hawaiian in the plantation camps. Workers cooked adobo and pinakbet, planted gardens behind their barracks, and held fiestas that gave them a sense of home. Filipinos would go on to become Hawaii’s largest Asian group, but their story was written in sweat, calloused hands, and sacrifice.

When histories intertwine

Hawaii’s sugar plantations were a crossroads of worlds. White owners and German businessmen oversaw the fields. Native Hawaiians, stripped of much of their land, worked alongside immigrants from Portugal, China, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. Labor strikes and struggles for fair wages slowly reshaped life in the islands, creating solidarity among workers of all backgrounds.

Over generations, these sharp racial and class lines began to blur. German families intermarried with Hawaiians and Asians, and today, German surnames are found in Filipino, Hawaiian, and mixed-race families alike. My own family’s story exists in that mix. The plantations that profited German entrepreneurs also became the foundation for Filipino resilience, survival, and eventual upward mobility.

Reading between the colors

This Census map tells a powerful story of migration and settlement. It shows how white Americans spread across the mainland, how waves of Germans, Irish, and English immigrants carved out space for themselves. But the map leaves out the histories of Indigenous peoples, Black communities, and the Asian and Pacific Islander workers who labored to build much of America’s wealth.

Hawaii’s history is tied to these colors, even if it is not visible here. The blue for German ancestry connects to Hawaii’s sugar barons. The yellow for English roots ties to missionaries and merchants who overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy. Every shade tells a story of power, migration, and change.

For me, this map is a reminder that our histories are bound together. The Germans who built Hawaii’s sugar industry set the stage for Ilocano migration. The Ilocano laborers who toiled in the cane fields carved out a future for families like mine. And today, these intertwined legacies live on in the faces, languages, and traditions of Hawaii’s people.