My political hero? Mayor Fasi gets it done

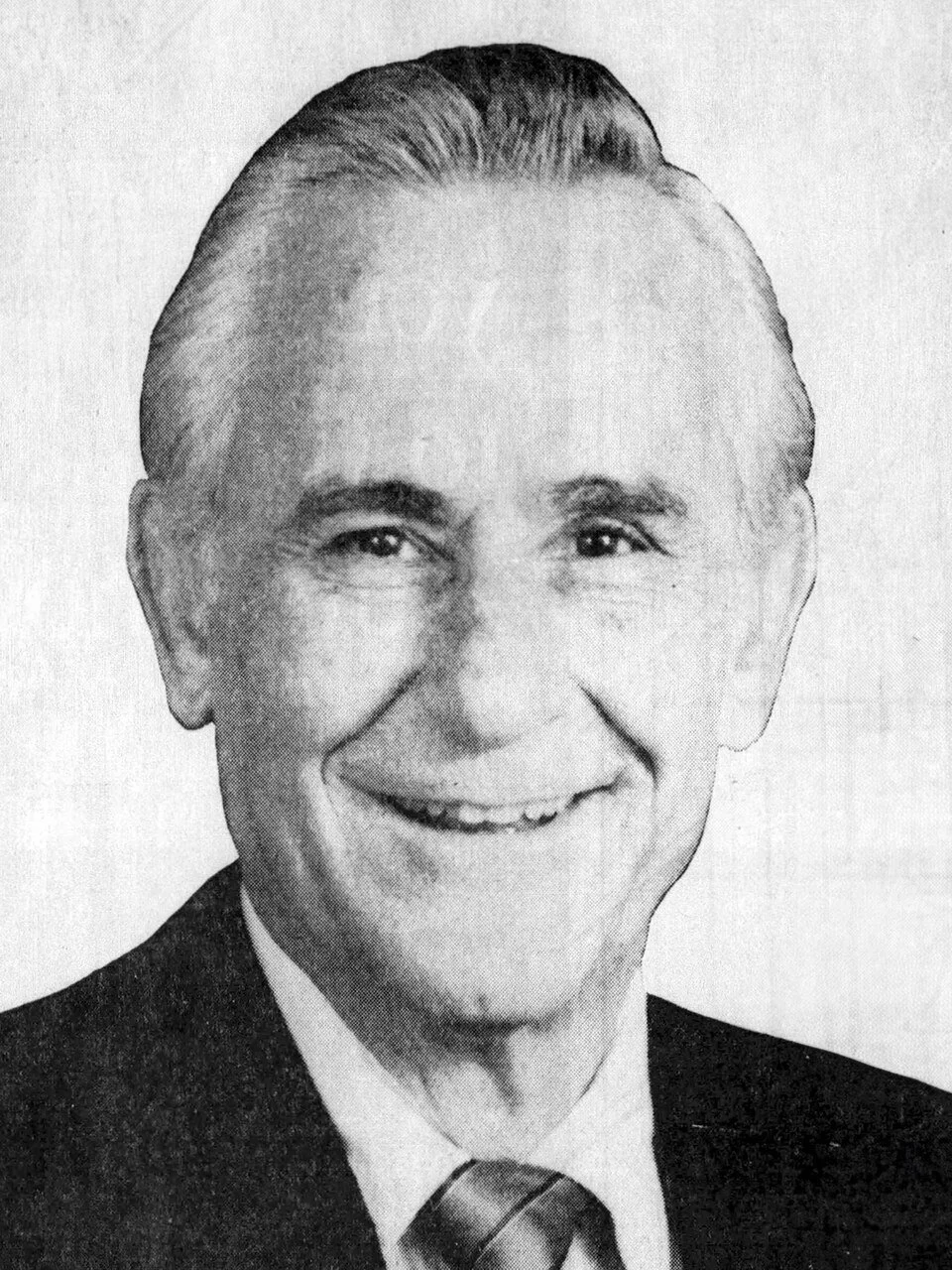

Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi. He was also a member of Rotary International–an organization in which I now serve as a president. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

I’m entering what I suppose you could call younger middle-age, that phase of life where you start to reflect on the figures who shaped your understanding of how the world works.

Growing up in Honolulu, Frank Fasi was simply part of the landscape—this larger-than-life mayor who seemed to be everywhere, doing everything, fighting with everyone.

I’ve spent half my life since then in Chicago, a city with its own legendary brand of politics and powerful figures, and that distance has given me perspective on what made Fasi special.

Watching him work during his time in office taught me more about leadership than any textbook ever could.

Yes, he had his faults—plenty of them—but that’s exactly why his lessons were so valuable. Real leadership isn’t about being perfect; it’s about being effective despite your imperfections.

Fasi was the son of Sicilian immigrants, worked in his father’s ice business from age eleven, served as a Marine in World War II, and then came to Hawaii to build a construction and salvage business before entering politics.

He understood what it meant to work for everything you got, and he never forgot where he came from.

“I haven’t forgotten my roots,” he used to say, and you could see it in every decision he made.

He genuinely fought for “the little guy” because he had been one himself.

The first thing Fasi taught me was that persistence trumps perfection.

The man lost more elections than he won—mayor races in 1952, 1980, 1996, 2000, and 2004, plus four unsuccessful runs for governor. But he kept coming back.

When Eileen Anderson defeated him in 1980, instead of sulking away, he switched from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party and came roaring back to defeat her in 1984.

At 84 years old, he was still running for mayor in 2004. That kind of resilience in the face of defeat is rare.

Most politicians disappear after one or two losses, but Fasi understood that public service wasn’t about ego (though he had one, for sure)—it was about the work itself.

What impressed me most was his willingness to be unconventional when convention wasn’t serving the people.

When the private bus company went on strike and was holding the city hostage, Fasi didn’t negotiate endlessly or form committees to study the problem. He created TheBus, a municipal transportation system that still serves Honolulu today. In fact, the system he built won international awards for transit systems until they were told they can’t win it anymore—give others a chance.

When he decided the city needed green space around City Hall, he didn’t wait for months of planning meetings. Legend has it he got a bulldozer one weekend and ripped up the parking lots on Hotel Street. City Council members came to work Monday morning with nowhere to park, and Fasi loved it.

Sometimes I think when Chicago’s Mayor Richard M. Daley did the same to Meigs Field—Chicago’s commuter airport in downtown Chicago—he was channeling Fasi.

Fasi understood that sometimes you have to break things to build something better.

He also showed me what accessibility in leadership really looks like.

As a kid growing up in Honolulu, I remember seeing him at community events, always surrounded by people, always listening. Every morning, you could find him at Heidi’s coffee shop at Bishop Square, sitting at an outside table with his aide, talking to anyone about anything. My dad had sat with him several times just to shoot the breeze or as we say in Hawaii, “talk story.”

He didn’t hold court in some ivory tower—he was out there with regular people, listening to their concerns, getting his pulse on the city.

Having lived in Chicago for half my life now, I’ve seen a different style of politics—more insular, more machine-oriented, where access to power often depends on who you know.

Fasi’s approach was the opposite.

That wasn’t just good politics; it was good leadership. How can you serve people you don’t actually know or talk to?

The shaka hand gesture became synonymous with Fasi’s administration because he put it on all city signs and publications. Some people thought it was hokey, but I—and others—saw it as genius.

He took something authentically local to Hawaii and made it a symbol of city government, connecting civic pride with local culture in a way that felt natural, not forced.

He understood that leadership is partly about symbols and partly about making people feel seen and represented.

The shaka symbol was used as a municipal device during Fasi’s tenure. Image recreation: Gerald Farinas.

But perhaps the most important lesson Fasi taught me was that you don’t have to choose between being tough and being caring.

The newspapers called him a “firebrand” and “combative,” and he was.

He would bulldoze opposition when necessary, switch parties when it served his purposes, and wasn’t afraid to make enemies. (Did I mention his ego?)

But he also created the Summer Fun program for kids and the Honolulu City Lights festival that families still enjoy today.

He established one of the nation’s largest neighborhood board systems, giving regular citizens a voice in city governance.

He was tough enough to fight the powerful and tender enough to create magic for children.

Fasi wasn’t perfect—far from it.

He could be ruthless, opportunistic, and self-promoting. He absolutely had room for ego, and yes, he loved the spotlight and the power that came with the office.

He made enemies and burned bridges.

His career was marked by as many defeats as victories.

But here’s what I came to understand about his ego and self-promotion: it was ultimately in service of people who had no other advocates in the halls of power.

When you’re fighting for working families, small business owners, and ordinary citizens against entrenched interests, sometimes you need an outsized personality to break through.

The wealthy and well-connected have lobbyists and influence networks. Regular people had Frank Fasi—and he made sure everyone knew it.

His motto was “Fasi gets it done,” and that swagger, that willingness to put his name on everything, wasn’t just vanity.

It was a promise to the people who voted for him that they had someone who would fight as hard for their interests as the powerful fought for theirs.

Watching him work, I learned that leadership isn’t about being a saint. It’s about channeling your flaws and strengths toward something larger than yourself.

Sometimes ego and self-promotion, when directed toward the right ends, can be tools of justice rather than just vanity.

It’s about showing up, again and again, especially when things don’t go your way.

It’s about remembering that public service is exactly that—service—even when your methods might be unconventional or your personality might rub people the wrong way.

The man literally transformed Honolulu. The Neal Blaisdell Center, the H-POWER waste-to-energy plant, the Civic Center green space, TheBus, the satellite city hall system—these weren’t just projects, they were investments in the community’s future.

Some of his initiatives failed, some of his campaigns ended in defeat, but the sum total of his work made life better for hundreds of thousands of people.

As I find myself in this phase of life where I’m starting to reflect on the leaders who shaped my understanding of what leadership can be, Frank Fasi stands out not because he was perfect, but because he was effective.

Having experienced both Honolulu and Chicago politics, I’ve seen different models of how power operates—the machine politics of the Midwest versus the more freewheeling, personality-driven style of island politics.

But Fasi taught me that real leadership requires the courage to fail, the persistence to keep trying, the humility to listen to ordinary people, and the vision to see what a community could become rather than just what it is.

Maybe that approach seems quaint now in our current political climate, where everything seems to be about image and positioning rather than actual accomplishment.

But having grown up watching Fasi and then observing politics in another major American city, I miss that kind of leadership—flawed, human, stubborn, and utterly committed to getting things done.

We could use a few more Frank Fasis in the world, complete with all their complicated contradictions.

After all, the best leaders aren’t the ones without faults.

They’re the ones who use their strengths to serve others despite their faults.

Fasi understood that, and growing up watching him navigate twenty-two years of leading a major American city, he taught me that lesson early.

Sometimes the best education comes not from perfection, but from watching someone stumble, get back up, and keep fighting for what they believe in.

That’s the kind of leader I’ve tried to be in my own work.

Thanks for that lesson, Mayor Fasi—it’s served me well in two very different cities, each with their own ways of getting things done.