Crunchy roll: Short history of lumpia—and why Ilocanos make the best

Photo: Musfika Jahan/Public domain.

[Trigger Warning: Pro-Ilocano language.]

Every Filipino family has a version of lumpia even among those who can’t cook. But among Ilocanos, this dish is more than a staple. It’s a point of pride.

Crispy, garlicky (that’s the Ilocano part), and often served with sukang Iloko (our unique Ilocano vinegar), lumpia in Ilocano kitchens has been elevated to an art form.

Tagalogs and Visayans like to claim theirs are the best. But really?!

While spring rolls originated in China, Ilocanos took the concept and transformed it into something uniquely their own.

Enter the Chinese traders

The story of lumpia traces back to centuries of cultural exchange.

Chinese traders introduced spring rolls to the archipelago’s disparate ethnolinguistic tribes and regions, and over time, these cooks reimagined the dish using native ingredients and flavors.

In the Ilocos where its people were specifically tied to the sea trade, the recipe became a testament to resourcefulness: families could stretch a handful of vegetables and a bit of meat into dozens of rolls, creating a dish that was as practical as it was delicious.

With garlic-forward seasoning (the Ilocos is one of the world’s largest garlic producers) and the signature sukang Iloko, vinegar made from sugarcane (once the largest sugarcane producers in the archipelago), this humble roll became an icon.

There are countless variations throughout the archipelago, each with its own personality.

Non-Ilocano versions

Made famous in Manila where the oldest Chinatown in the world exists, lumpiang Shanghai took the lead as a Filipino favorite for its basicness.

It features finely minced pork and vegetables stuffed into spring roll wrappers. While Ilocanos feature savory dips, those Tagalogs loved to dip their lumpiang Shanghai in sweet sauces.

On the U.S. mainland, this is the most popular and is often served at parties because it’s the easiest to make.

Lumpiang sariwa is not fried at all. Sariwa is the Tagalog word for “fresh.” This version is wrapped in an egg crepe and topped with peanut sauce. It offers a lighter experience. Though, I’ve seen some folks really drench the sweetened peanut sauce on theirs.

Lumpiang ubod is also commonly eaten with a sweetened peanut sauce. Ubod refers to the tender heart of palm, the featured vegetable in this lumpia.

This version originates south of Manila in the central parts of the archipelago. This is where coconut palms have been grown and harvested for hundreds of years.

Moving farther south, lumpiang togue features an ingredient common among India-influenced parts of the archipelago: mung beans.

Also common in the southern islands is spice! So this lumpia is often dipped in chili-flavored sauces.

Dessert lumpia? Turon, a sweet take, features caramelized saba bananas grown in the really hot tropical parts of the far south. And jackfruit is sometimes added for texture and sweetness.

And finally, there is what a couple awful Californians I know call, lumpiang Panda Express. [Honestly, their Filipino cards need to be revoked.]

Global lumpia

Lumpia’s story is part of a larger global story of spring rolls.

In Taiwan, you’ll find lumpia’s ancestor popiah. It’s a soft crepe filled with vegetables, meats, and a sprinkle of peanut powder, traditionally eaten during Qingming Festival.

In Hong Kong, spring rolls are a celebrated dim sum item. Its fillings are simple and light and dipped in soy sauces.

But it is in Hawaii where lumpia truly found a second home, especially in communities with strong Ilocano roots. From church fundraisers to family luaus, trays of lumpia are as much a part of Hawaiian celebrations as malasadas or plate lunches.

Glorious crunchy rolls

What began as a simple roll has become a cultural symbol. Lumpia reflects centuries of migration, trade, adaptation, and culinary creativity. From Baguio to Honolulu, from Chicago to Madrid, you’ll find a version of it made by your local Filipino family.

Wherever people from the archipelago settle in the world, lumpia follows, bridging tradition and innovation one perfectly wrapped, perfectly fried bite at a time. [Even if the lumpia isn’t Ilocano.]

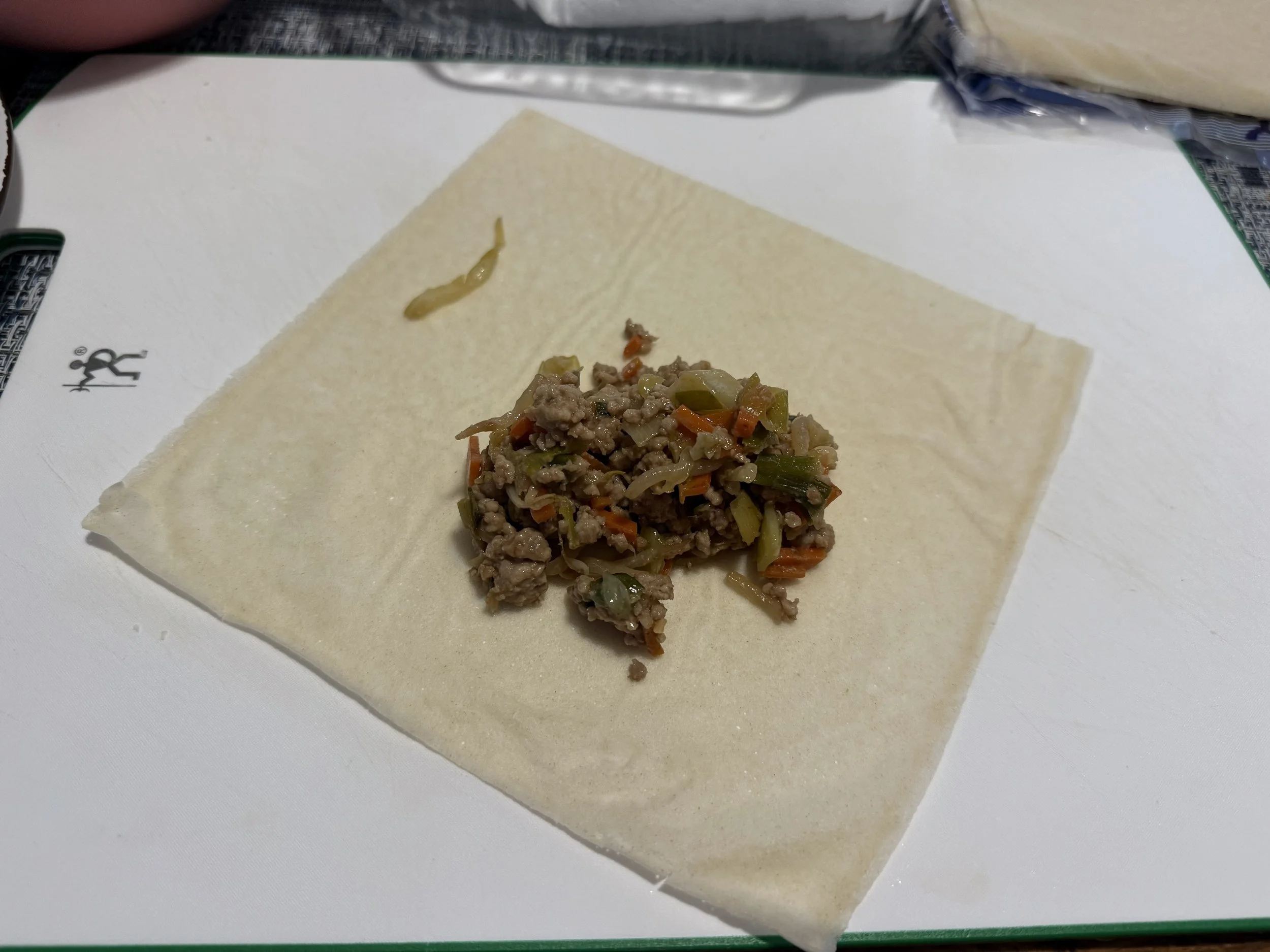

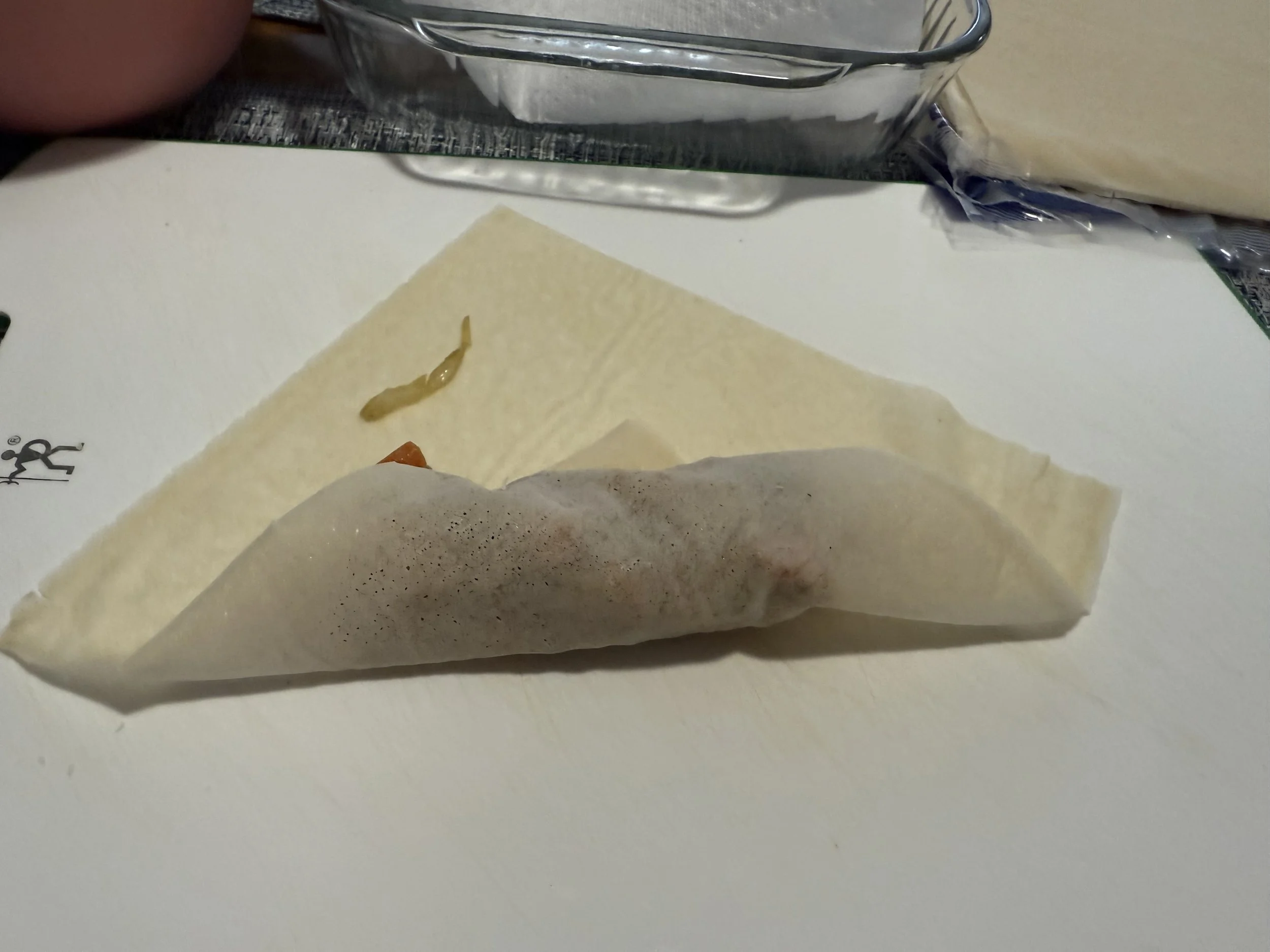

My own lumpia making skills

No recipe because why would I give you my secret recipe?! Also, I left out the secret ingredients.